Equity in career technical education is increasingly treated as a claim that must be demonstrated, not simply asserted. Districts are asked to show, with disaggregated evidence, that students from special populations can access high-quality programs and work-based learning opportunities at rates that resemble their peers. That request sounds uncomplicated until we confront the methodological friction that many systems create: the data needed to answer equity questions often lives across spreadsheets, emails, paper logs, and disconnected tools.

That fragmentation produces a quiet research problem inside everyday practice. We have many theories about why disparities emerge, but far fewer shared conventions for how districts should operationalize “equitable participation” in CTE and work-based learning across time, schools, pathways, and sites. Given that local conditions vary, an equity analysis cannot rely on districtwide totals alone. It requires measurement systems that can surface CTE participation gaps that staff may not know exist, and it requires governance that keeps those measures stable enough to interpret.

In what follows, we approach equity in career technical education as a measurement and design problem that intersects with compliance requirements, program improvement, and the ethics of data use. We outline a practical analytic framework, clarify methodological considerations that shape what we can responsibly claim, and propose a workflow that districts can sustain across the Perkins V CLNA cycle. We also reference how TitanWBL supports this work by treating data infrastructure as an enabling condition for equity inquiry, not an afterthought.

Why equity in career technical education is a measurement problem

Equity is sometimes reduced to a single question: “Are students from each subgroup enrolled?” That framing is attractive because it is easy to report. It is also incomplete. In CTE and work-based learning, participation is influenced by scheduling, transportation, prerequisites, counselor recommendations, employer expectations, and program availability. As a result, enrollment totals can reflect both opportunity structures and student choice, often in ways that are difficult to disentangle.

Two measurement issues appear repeatedly when districts attempt to study equity patterns. First, participation is often used as a proxy for access, yet participation and access are not identical. Second, the direction of subgroup gaps is not stable across contexts, which means a single narrative about “who is underrepresented” can mislead. If we want equity in career technical education to be a discipline of continuous improvement rather than an annual reporting event, then we need operational measures that capture where inequities accumulate across a student’s pathway.

From access to outcomes: a usable equity framework for CTE analytics

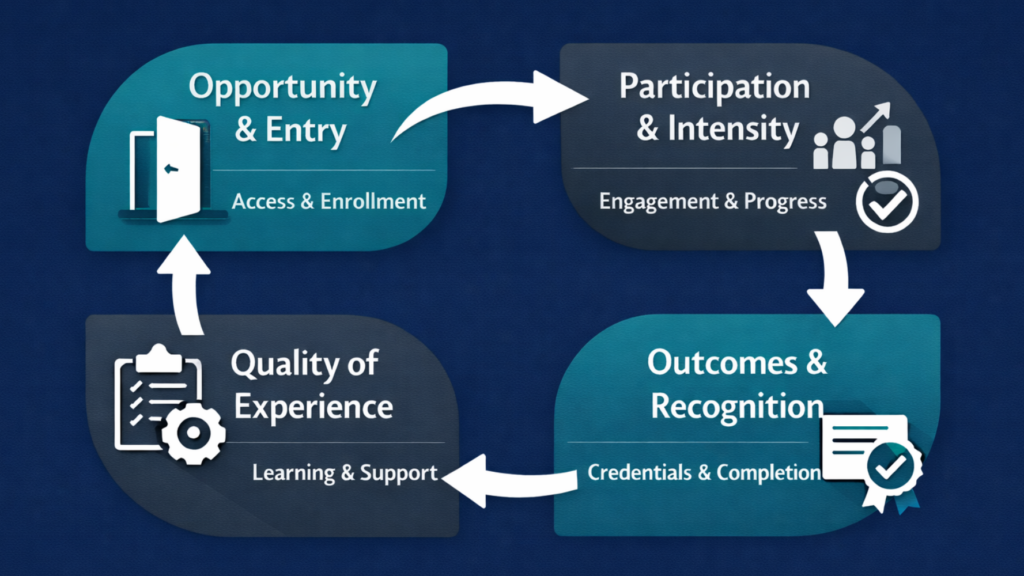

A helpful move in the research literature is to treat equity as multi-dimensional. Frameworks in the field commonly distinguish between equity in access and participation, equity in credential attainment, and equity in longer-run outcomes. This matters because a district can look equitable at entry and still reproduce inequity through differential experience quality, differential intensity of participation, or differential recognition of learning.

For district teams, we can translate those domains into a small set of recurring analytic questions. The goal is not to claim that every domain is perfectly measurable. The goal is to create a stable inquiry structure that can be revisited each semester and each CLNA cycle.

A four-domain equity lens that districts can operationalize

- Opportunity and entry: Who can enroll, and under what constraints? Do prerequisites, scheduling conflicts, or transportation barriers predict who participates?

- Participation and intensity: Once students enter, who becomes a concentrator and who exits early? Do gaps widen as experiences become more time-intensive?

- Quality of experience: Who receives placements that are aligned to a program of study, supervised, and documented? Who receives low-signal placements that function mainly as exposure?

- Outcomes and recognition: Who earns industry-recognized credentials, completes verified hours, or demonstrates competencies that can be reported with confidence?

This lens has a practical implication. Equity in career technical education requires connecting student attributes to experience attributes and outcome attributes over time. If those data live in separate tools, the analysis tends to collapse into the lowest common denominator: simple counts.

How spreadsheets can hide CTE participation gaps

Spreadsheets are not inherently flawed. They are often appropriate for pilots, early-stage programs, and limited reporting needs. The problem is that equity in career technical education is rarely a one-time analysis. It is longitudinal, disaggregated, and sensitive to definitions. That combination creates failure modes that teams recognize only after a reporting deadline arrives.

TitanWBL’s blog has addressed this operational ceiling directly in The Hidden Cost of Spreadsheets in Work-Based Learning Programs, which outlines why version control, manual merges, and missing records become systemic as programs scale. The equity problem is that these issues are not distributed evenly. Missingness and inconsistencies often cluster in predictable ways that correlate with subgroup status, school context, or placement type.

Three mechanisms commonly explain why spreadsheet-based workflows obscure inequities even when staff are acting in good faith.

Aggregation flattens variation

Equity concerns often emerge at the intersection of subgroup, pathway, school, and experience type. Aggregating to a district total can hide variation that is analytically meaningful, such as a participation gap that exists only within a particular pathway at a particular high school. Even disaggregating by a single demographic variable may miss intersectional patterns, which can matter for improvement planning.

Missingness is rarely random

Work-based learning data is especially vulnerable to missingness because it depends on documentation and verification. Hours may go unrecorded when a placement changes, when supervision is inconsistent, or when documentation is burdensome. Those conditions can correlate with disability status, language status, or economic constraints. If missingness is systematically patterned, then descriptive equity analyses become biased in ways that are hard to detect after the fact.

Definitions drift over time

Terms that appear stable, such as “concentrator,” “qualifying experience,” or “high-quality placement,” often vary by state rules and local practice. In spreadsheet workflows, definitions can live in staff memory rather than as standardized fields, which increases drift as personnel changes. This is one reason why teams can struggle to interpret whether an observed gap is a real change or an artifact of changing measurement.

Methodological considerations that strengthen equity claims

Equity analysis can become performative if disaggregation is treated as the endpoint. Disaggregation is necessary, but it does not automatically explain a gap or justify an intervention. Given that, it helps to be explicit about the methodological choices that shape interpretation.

Disaggregation choices shape what we can responsibly claim

Many districts begin with Perkins-defined special populations because those categories align with compliance requirements. That is sensible for the Perkins V CLNA, but local equity questions may require additional lenses depending on demographics and pathway offerings. We also need to decide whether subgroup status is treated as static. For example, English learner status can change over time. Treating it as fixed may distort trend interpretation.

Small n and privacy constraints are real limitations

At the pathway or site level, subgroup counts can be small. Small n makes estimates unstable and raises privacy risks. Districts can address this by using multi-year rolling averages, transparent category collapsing, and suppression rules consistent with policy. The analytic goal is to learn without overstating precision.

Participation gaps are descriptive signals, not causal conclusions

A common misunderstanding is to interpret a descriptive gap as proof that a program causes inequity. Participation gaps may reflect uneven access, differential advising, transportation constraints, or student preferences shaped by prior experiences. A more defensible stance is conditional. If we observe that students with IEPs are underrepresented in high-signal placements, then we have identified a disparity that warrants investigation. That finding alone does not identify the mechanism.

Quality needs operational definitions

Equity in career technical education becomes more meaningful when we define what counts as a high-quality experience. District teams often disagree here, and that disagreement is not inherently a problem. It becomes a problem when the definition is implicit. A practical approach is to adopt a tiered rubric so that not every experience is treated as equivalent.

For example, a rubric might incorporate minimum verified hours, alignment to a program of study, documented supervision, and evidence of skill development. These indicators are not perfect proxies for learning, but they can be made stable enough to track over time.

A counterpoint worth taking seriously

Some colleagues argue that better data systems can intensify surveillance or produce deficit narratives. That critique matters. If equity dashboards become tools for blaming schools or labeling students without context, then the analytic work can do harm. Governance practices can reduce this risk. Role-based access, transparent definitions, and shared interpretation protocols shift the function of data from policing to redesigning opportunity structures.

A practical workflow for equity monitoring across the WBL lifecycle

If equity in career technical education is to be sustained, it has to be routinized. The workflow below is designed to be feasible for district teams that are already stretched. It emphasizes a small number of recurring questions, stable definitions, and a feedback loop that connects observed gaps to plausible mechanisms and documented interventions.

1) Create a stable link between student profiles and experience records

Equity monitoring requires demographic data that districts already hold, typically in the Student Information System (SIS). The technical challenge is joining SIS data to work-based learning records without repeated manual merges. TitanWBL supports SIS integration so that experience records can remain linked to student profiles as data updates over time. This reduces the risk that equity monitoring collapses into spreadsheet crosswalks that break each reporting cycle.

2) Define auditable quality tiers

Operational definitions work best when they are auditable. A small set of indicators is often sufficient to differentiate experience types and quality levels.

- Verified hours (student logs hours; supervisor verifies)

- Experience type (job shadowing, internship, apprenticeship, clinical rotation)

- Pathway alignment (aligned, partially aligned, not aligned)

- Supervision and supports (documented supervisor; accommodations recorded when appropriate)

If our indicators are stable, then equity analysis can move beyond “who participated” toward “who received which kinds of opportunities.”

3) Build an equity dashboard that answers a short list of questions

A strong equity dashboard does not attempt to answer everything. It focuses on the questions that recur across planning, reporting, and improvement cycles.

- Representation: Does subgroup participation in each pathway resemble the subgroup’s share of the eligible population?

- Intensity: Once enrolled, do subgroups complete comparable hours and progress through comparable sequences?

- Quality: Do subgroups receive comparable access to high-quality placements, not only any placement?

- Outcomes: Are there gaps in credential attainment, verified participation, or pathway completion?

District teams often report that the first year of implementation is where the biggest analytic shift occurs. The post What Districts Learn in Their First Year After TitanWBL Implementation describes how shared visibility changes what teams notice and how quickly they can respond to inequities that previously required weeks of manual work.

4) Treat observed gaps as hypotheses, then investigate mechanisms

Once a disparity becomes visible, the next step is to resist the urge to jump directly to solutions. A gap is often best treated as a hypothesis generator.

If female students are underrepresented in manufacturing placements, then we can examine recruitment materials, referral practices, prerequisites, and employer expectations. If English learners complete fewer verified hours, then we can examine documentation burden, transportation logistics, supervisor communication, and placement supports. This approach aligns with the logic of applied research: descriptive patterns guide deeper inquiry.

5) Document interventions and monitor whether gaps narrow

Equity work is weakened when interventions are not documented. If a district pilots transportation supports, revises advising protocols, or changes employer screening practices, then it should be possible to track whether participation patterns shift in later cohorts. Centralized tracking enables districts to evaluate whether a gap narrows, even when causal claims remain modest.

Equity, compliance, and the Perkins V CLNA

Equity in career technical education is not only a moral or pedagogical concern. It is embedded in accountability logic tied to funding. Perkins V emphasizes disaggregated reporting, local improvement planning, and a Comprehensive Local Needs Assessment (CLNA) that explicitly examines access and performance for special populations. The legislation and resources hosted by the Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education provide the federal backbone for these requirements. See Perkins V (OCTAE) for the official overview and related guidance.

For practical implementation, many districts use structured equity gap analysis guides. NAPE’s brief on local equity gap analysis is a useful reference because it connects disaggregation to the CLNA, local performance targets, and improvement planning. The document is available here: Perkins V Equity Gap Analysis (Local) at a Glance.

One implication is practical: if a district waits until the CLNA deadline, it will often rely on limited proxies. If the district monitors equity patterns routinely, then the CLNA can become synthesis rather than crisis. The TitanWBL post How to Use Your WBL Data to Secure Perkins V and Grant Funding makes this point from a funding perspective, showing how disaggregated WBL data can support CLNA narratives and targeted requests to close identified gaps.

What data infrastructure can and cannot do

We should be candid about limits. Better measurement can reveal disparities, but it does not remove the structural barriers that generate them. Transportation constraints, scheduling structures, employer discrimination, uneven pathway availability, and staffing limitations still shape access. Data can support redesign, but it does not guarantee redesign.

There is also a compliance trap. If the goal becomes producing the right chart rather than improving the conditions of participation, equity analytics can drift away from student experience. This is one reason we emphasize routine monitoring paired with documented interventions. The analytic work should remain connected to a theory of change, even if that theory is locally developed.

Still, infrastructure is not a minor detail. When districts rely on manual systems, they often face what TitanWBL describes as the “spreadsheet ceiling,” where administrative burden constrains program growth. The article Why Districts Struggle to Scale Work-Based Learning Programs connects this capacity issue to equity, arguing that districts cannot promise broad access if they cannot track and validate participation reliably at scale.

Future directions for stronger equity evidence in CTE

Research on equity in career technical education is moving toward more precise questions about mechanisms and outcomes. District practice can move in parallel, even when local capacity differs from research capacity.

Linking experiences to longer-term outcomes

Many districts can measure participation and verified hours, but fewer can link those measures to postsecondary persistence or labor market outcomes in a consistent way. As state longitudinal data systems mature, it may become easier to align CTE participation patterns with postsecondary enrollment or wage records, though privacy and governance remain constraints.

Evaluating interventions with stronger designs

When districts implement targeted supports, they can sometimes embed stronger designs, such as phased rollouts across schools or interrupted time-series analyses. These designs do not resolve all selection bias, but they can strengthen inferences beyond simple before-and-after comparisons.

Shifting from “who participated” to “what students learned”

A persistent limitation is that participation data does not directly capture learning quality. Some districts are experimenting with competency-based documentation, structured reflection artifacts, and employer feedback. If these measures can be standardized, equity monitoring can focus more directly on learning opportunity rather than only enrollment and hours.

Data governance as an equity practice

Data governance is often treated as an IT concern. In equity work, governance is substantive. Who has access, how categories are defined, how analyses are interpreted, and how results are communicated all shape whether data supports improvement or blame. This is why compliance-oriented tools should also provide transparency, audit trails, and role-based access, not only dashboards.

For districts thinking about governance through a compliance lens, the TitanWBL post The Compliance Risk No District Talks About in Work-Based Learning Reporting outlines why fragmented reporting processes increase both audit risk and equity blind spots.

Conclusion

Equity in career technical education increasingly requires evidence that is disaggregated, longitudinal, and sensitive to context. Participation is a useful starting point, but it is not enough. If we want to close opportunity gaps, we need to see where inequities accumulate across entry, intensity, experience quality, and outcomes.

A sustainable approach begins with stable linkages between student profiles and experience records, explicit definitions of quality, and dashboards that answer a small set of recurring questions. From there, observed gaps can be treated as hypotheses that prompt investigation, followed by documented interventions and monitoring. TitanWBL’s emphasis on centralized tracking and query-based analysis is designed to make that workflow feasible, particularly for districts that have outgrown spreadsheet-based systems.

If our field is serious about closing gaps, the next step for many districts is not collecting more data. It is collecting better-connected data under clearer definitions, with governance that supports improvement. That is how equity in career technical education becomes visible enough to act on.

Sources

- Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE). Perkins V legislation and resources.

- National Alliance for Partnerships in Equity (NAPE). Perkins V Equity Gap Analysis (Local) at a Glance.

- Office of Community College Research and Leadership (OCCRL), University of Illinois. CTE Gateway to Equity.

- CTE Research Network. Building district work-based learning data systems (District WBL DataSys).